Originally published in the New York Times and Nashville Tennessean on Sunday, 11/21/99

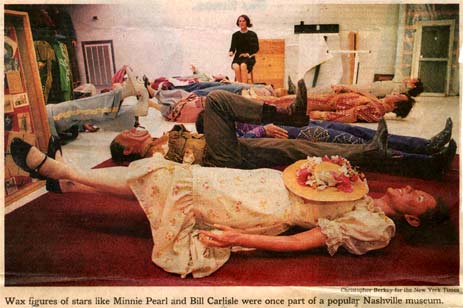

Wax treasure trove sleeps below museum

By Neil Strauss / New York Times News Service 11/21/99

NASHVILLE -- Where do wax figures go when they die?

For more than a quarter of a century, the Country Music Wax Museum was one

of Nashville's most colorful tourist magnets. One in every nine visitors to

Nashville walked through its doors, gawking at life-size replicas of Hank

Williams, George Jones and Dolly Parton.

This was no ordinary wax museum. Performers like Minnie Pearl and Johnny

Cash donated clothes and instruments and even tended to their characters.

Once, after Jim Reeves had died and his ex-wife dropped by to brush the hair

on his exhibit, employees saw she had put a picture of herself on the mantel.

But the Country Music Wax Museum quietly shut its doors two years ago, a

casualty of Nashville's self-conscious rush toward modernization. In 1971,

when the museum opened, Nashville was a small city with a handful of studios;

today the population of the metropolitan area has boomed past 1 million, and

there are 400 music studios. Professional hockey and football teams have moved

into town, and health care has replaced country music as the city's No. 1

moneymaker.

The wax museum was once part of a thriving tourist mall, along with the

Hank Williams Jr. Museum, Barbara Mandrell Country and the Car Collectors Hall

of Fame. Now they, too, are closed, and there are plans to supplant them with

a traffic circle, offices and a Ritz-Carlton hotel.

But what happened to the cherished wax figures of country music greats with

their vintage finery and original instruments?

Not even officials of the Country Music Hall of Fame across the street knew

the answer. This reporter crisscrossed Nashville on the trail of the missing

wax figures, encountering tales of a vanished promoter, a Kennedy campaign

consultant and a Taiwanese herb vendor. But nothing could prepare him for what

he found.

None of the three shopkeepers who remain in the area -- once called the

gateway to Music Row but now nicknamed "death row" -- knew the figures'

whereabouts. Rumor had it that they had been sold to the Music Valley Wax

Museum, a newer attraction on the city's outskirts, where the Opryland USA

theme park, since demolished, had lured the tourists who once kept the mall's

shops in business.

"They did offer their collection to us," said Doris Harvey, the assistant

manager of the Music Valley Wax Museum. "But they didn't want to break the

set, and we already had many of the same figures."

Inquiries at the Country Music Hall of Fame revealed little. Administrators

said they were never offered the figures. But one employee brought out a

charmingly crude wax museum coloring book she had recently bought for 99 cents

at the local grocery.

Phone calls to former employees of the museum produced the vague conjecture

that the figures had been melted down.

More than 60 figures were missing. And it wasn't so surprising in a city

that likes to reinvent itself every few years, complaining about the loss of

tradition while paving over its past.

"The city decided that they want the convention business," said Jim Cook,

the owner of Hat Country, a wax museum neighbor that is going out of business.

"But they can't create that new image of Nashville without killing the old

one."

Years ago the Country Music Wax Museum was tied to the most powerful people

in the city. Aurora Publishing, a failed book and entertainment venture that

had managed to pull most of Nashville into its orbit, founded the museum. One

of its first chiefs was Paul Corbin, a political operative who worked on

campaigns for John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy. After their

assassinations, Corbin found respite from politics in wax figures, often

borrowing their boots to wear around town.

But the museum's most notorious operator was Dominic DeLorenzo, an Aurora

founder described by former employees as a good-looking, slick-talking charmer

who persuaded Nashville luminaries like Chet Atkins, Minnie Pearl and the

newspaper mogul John Seigenthaler to invest in the publishing company and

museum. It was while dining at the Peking Restaurant, a country star hangout,

that DeLorenzo discovered the museum's future: Daniel Hsu, the son of a

leading herbal medicine authority from Taiwan, who had given up his

microbiology studies at Vanderbilt University to open the restaurant.

Hsu soon became majority shareholder in Aurora, and DeLorenzo left

Nashville for New York and disappeared, leaving behind a pile of creditors,

some of whom believe that he faked his death. DeLorenzo's son, Dominick, who

used to spend his summers working at the museum, said his father died of

cancer in 1980.

Under Hsu, the wax museum thrived and the area around it blossomed into a

tourist mecca of offbeat novelty stores and shrines to country stars. In a

bold move in a world of Hank Williams Jr. fans, Hsu opened a Chinese art

museum above the wax museum. And when Hsu learned that Seigenthaler's

sister-in-law was an artist, he commissioned her to make new wax figures.

The last one she made was of George Strait. A faded wood sign above the old

museum still advertises the addition to the collection.

With Opryland closing, tourism slumping, the Hall of Fame moving downtown

and tour buses rerouting to the more package-tour-friendly Branson, Mo., the

death knell for the neighborhood rang in 1997 when a city-sponsored study

determined that a business district would be more useful.

By then, Hsu had left to work for his family's herbal medicine business in

California, selling the buildings to a developer named Jim Caden, who

converted them into office space and a shoe store.

"They all wanted us out of there," said Phyllis Shoemake, a former wax

museum employee who now distributes herbal medicines, including Hsu's. "They

thought we were an eyesore. Now it's a ghost town."

One of Caden's office buildings became home to a magazine called Country

Weekly. And it was there that the trail of the wax figures got warm again.

Visitors reported seeing the Hank Williams dummy in the reception area,

leaning against the wall in his original suit designed by Nudie the Rodeo

Tailor.

And, sure enough, a reporter for Country Weekly, Bob Cannon, knew exactly

where the figures were: They had never left the building and were locked up,

deteriorating, in the basement. "The weird thing is, if you go down there at

night, it's real spooky," he said. "You have 40 wax figures looking at you.

And they all look like Buddy Ebsen, whether they're male or female."

After ignoring phone calls for a week, Caden eventually agreed to open the

storage room, which was once home to the car collectors' museum. "But," he

warned as he unlocked the door, "I don't want you to write anything making

fun of the South, or some of the positions these figures are in."

Inside, the pieces looked more as if they belonged to a country music

chamber of horrors than a wax museum.

"That," said Michael Horton, the building's maintenance man, "was Ronnie

He gestured to a wax face that had been smashed by vandals. Barbara

Mandrell's head, with a hairpiece she had designed, was impaled on a stick,

yards away from her torso. Johnny Cash, all in black, stood against the wall,

one arm hanging below his knee. Pop Stoneman's autoharp rested on a bench,

covered with detached fingers. Uncle Dave Macon's gold teeth had been stolen.

And Hank Williams Jr. lay on his back with two disembodied hands across his

chest and a giant crack running along his neck.

Just who owns these figures -- 62 of them, not counting various busts and

body parts -- is in some doubt. Caden said they belonged to him, to Hsu or to

Aurora. "But I don't even know where Daniel Hsu is, to be quite honest," he

said. Hsu, who works in the Irvine, Calif., office of Brion, his family's herb

company, did not return phone calls.

Fortunately, Nashville's delinquents didn't recognize the value of what

they were vandalizing, and left the costumes intact. When Mark Medley, the

archivist for the Country Music Hall of Fame, walked into the storeroom to

determine the collection's worth, his jaw dropped. There were clothes from the

entire Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers' singing brakeman outfit, a rare Gretsch

guitar that once belonged to Jim Reeves, handwritten lyrics from the Stoneman

Family and more than a dozen stage suits by Nudie, the rhinestone-loving

designer who created country high-fashion in the late 1940s.

"This collection of suits is really the most complete I've ever seen,"

Medley said. "Their historical and monetary worth is considerable."

"It's so strange," he continued. "These things belonged to people who

are so exalted, and now their costumes end up on the floor."

Just how long they will stay on the floor is anybody's guess. "I don't

have a clue what I'm going to do with them," Caden said. "I thought some

bolt of lightning would strike us, and we would figure it out. But we really

have no plans."

And so the figures remain in limbo, a waxy analogy for country music itself

as they decay untended while Nashville races after its cosmopolitan dream.

Joseph Seigenthaler